Dr Claire McEvoy, Lecturer in Nutrition and Ageing Research, and Rebecca Townsend, PhD researcher, at the Centre for Public Health, Queen’s University Belfast, advise that it is never too early or never too late to adopt a brain healthy lifestyle! In this blog they highlight ways to slow down cognitive decline and delay or prevent dementia and why it is one of the most important public health priorities today.

Our brain controls how we learn and remember, think and feel, therefore looking after our brain is crucial for overall health and wellbeing. Dementia causes irreversible brain damage that affects memory and thinking skills as well as the ability to carry out everyday tasks. It’s one of the leading causes of death and disability across the Island of Ireland.

Currently, 86,000 people have been diagnosed with dementia and this number is set to double in the next 20 years largely because of population ageing. Given that there is currently no cure for dementia, identifying ways to slow down cognitive decline and delay or prevent dementia is one of the most important public health priorities facing Ireland today.

Why we should be optimistic about preventing dementia?

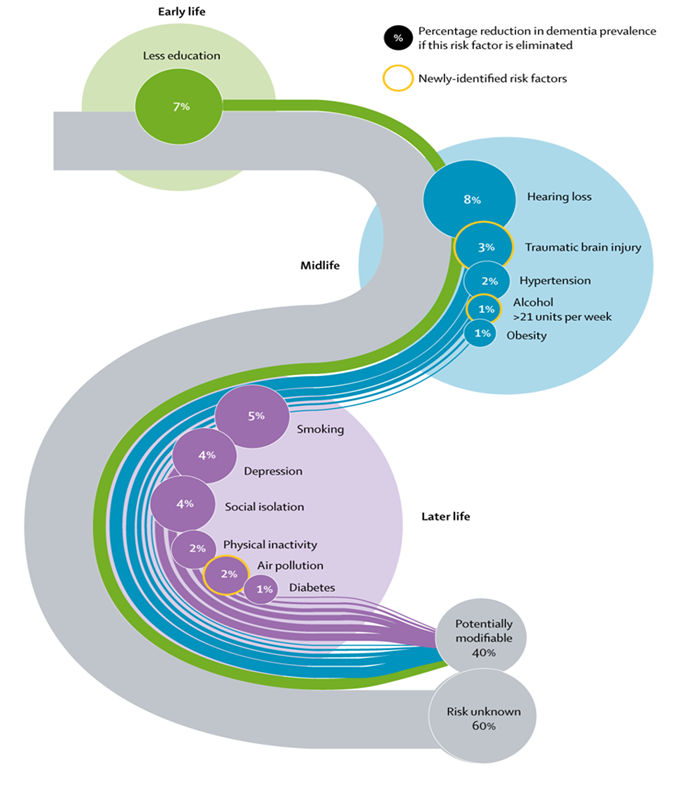

Previously, it was thought that dementia was largely determined by our age and genetic risk which we cannot control. But the recent ‘Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention’ evidence review identified 12 modifiable lifestyle and environmental factors for dementia1 including:

- diabetes,

- hypertension,

- obesity,

- physical inactivity,

- smoking,

- low quality education,

- heavy alcohol consumption,

- social isolation and depression,

- hearing loss,

- traumatic brain injury and

- air pollution.

If these modifiable risks are addressed, it could prevent up to 40% of future dementia cases in our population.

Livingstone et al. 2020. The Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention

What can we do now to adopt a brain-healthy lifestyle?

In addition to quitting smoking, correcting hearing loss, cutting back on alcohol and keeping a healthy body weight there are additional lifestyle choices below that can protect the brain against damage.

Eat a brain healthy diet

Choosing a healthy balanced diet is associated with a wide range of health benefits, and this includes brain health. Researchers are trying to better understand how specific dietary components influence brain functions. However, current evidence shows that ‘what’s good for the heart is also good for the brain’. A heart-healthy Mediterranean diet has been associated with slower cognitive decline and decreased dementia risk in later life2-3.

A Mediterranean diet means eating more wholegrains, legumes/pulses, vegetables, fruit, raw nuts and fish (preferably oily fish like sardines, mackerel, herring, salmon and trout) and using olive oil as the main fat source. These foods are rich in antioxidant vitamins and omega-3 fatty acids that are important to protect the brain cells from damage.

Eating processed meats, fried foods and confectionary less often also supports brain function. It is worth noting that vitamin supplements are no substitute for a healthy diet when it comes to brain health. Some people with nutrient deficiencies may experience cognitive benefit from supplementation. However, most people in the general population will derive greater brain health benefits from improving the quality of their usual diet rather than taking vitamin/food supplements4-5.

Keep physically active

Being physical active is protective for brain health. Exercise is associated with reduced shrinkage in the brain during ageing6, and reduced dementia risk in later life7. Exercise may benefit the brain by improving overall heart and metabolic health. There is also some evidence that exercise stimulates neurogenesis (the ability to grow new brain cells) within regions of the brain that are vulnerable to Alzheimer’s disease8. Aerobic exercise is thought to be most beneficial for brain health and this includes any activity that increases heart rate such as walking, dancing, housework or gardening.

Be socially and cognitively active

Keeping your brain active by learning new and challenging things can help to stimulate new connections within the brain and build ‘cognitive reserve’ or resilience against brain damage9. The more you can build cognitive reserve throughout life, the better equipped the brain is to deal with the loss of brain cells due to ageing or disease. Research suggest that participating in stimulating activities like puzzles, conversing and socialising with others regularly, and learning new things such as a language or musical instrument, are good ways to optimise brain health.

Latest evidence

The Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability (FINGER) was one of the first randomised control trials to demonstrate that a multi-domain lifestyle intervention could prevent cognitive decline10. Using a sample of 1260 individuals aged 60+ years from Finland, the trial ran for two years.

Those assigned to the intervention group were provided with advice on eating a healthy diet, a programme for physical activity and management for their heart health. After two years, participants in the intervention group had significantly less cognitive and functional decline, and a better overall health related quality of life compared to those in the control group10.

These findings are very promising but we need to understand if they can be replicated in other countries, where there are different cultures, lifestyle habits and health beliefs. In this regard, the BRAIN-Diabetes Study is a cross-border trial in Ireland coordinated by Queen’s University Belfast that is testing an adapted version of the FINGER intervention in people with type 2 diabetes living in border areas of Sligo/Leitrim/Tyrone/Fermanagh.

Why research on dementia matters

Accumulating scientific evidence provides an ideal opportunity to evaluate national policies, strategies and services for brain health in our population. To have a tangible impact on future dementia cases then dementia should be considered as a complex and multifactorial condition in a similar manner to other chronic conditions such as heart disease and stroke. We need to ensure that those at increased risk of poor brain health have access to the information, support, and services they need to enable them to adopt a brain healthy lifestyle.

It is vital that research continues to address evidence gaps for dementia prevention. This includes further exploration of factors such as; diet, sleep and social determinants that can influence brain health. We also need to understand how aware the general public are about modifiable risk factors and behaviours for brain health.

Do you want to rate your own brain health?

We invite you to take part in an ongoing study involving a short anonymous online survey that asks you questions about your lifestyle and provides you with a brain health score.

Importantly, the survey data can be used to inform the design of interventions and services that are needed and wanted by our population to look after their brain health and reduce the risk of dementia in later life.

If you want to learn more about brain health or our work please feel free to get in contact.

Dr Claire McEvoy (c.mcevoy@qub.ac.uk), Lecturer in Nutrition and Ageing Research

Ms Rebecca Townsend (rtownsend02@qub.ac.uk), PhD researcher

Centre for Public Health, Queen’s University Belfast.

References

- Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D, Ballard C, Banerjee S, Burns A, Cohen-Mansfield J, Cooper C. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. The Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2673-734.

- Wu L, Sun D. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and risk of developing cognitive disorders: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Scientific reports. 2017;7(1):1-9

- McEvoy CT, Hoang T, Sidney S, Steffen LM, Jacobs DR, Shikany JM, Wilkins JT, Yaffe K. Dietary patterns during adulthood and cognitive performance in midlife: The CARDIA study. Neurology. 2019;92(14):e1589-99.

- D’Cunha NM, Georgousopoulou EN, Dadigamuwage L, Kellett J, Panagiotakos DB, Thomas J, McKune AJ, Mellor DD, Naumovski N. Effect of long-term nutraceutical and dietary supplement use on cognition in the elderly: a 10-year systematic review of randomised controlled trials. British journal of nutrition. 2018;119(3):280-98.

- Rutjes AW, Denton DA, Di Nisio M, Chong LY, Abraham RP, Al‐Assaf AS, Anderson JL, Malik MA, Vernooij RW, Martínez G, Tabet N. Vitamin, and mineral supplementation for maintaining cognitive function in cognitively healthy people in mid and late life. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2018(12).

- Gu Y, Beato JM, Amarante E, Chesebro AG, Manly JJ, Schupf N, Mayeux RP, Brickman AM. Assessment of Leisure Time Physical Activity and Brain Health in a Multiethnic Cohort of Older Adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2026506.

- Blondell SJ, Hammersley-Mather R, Veerman JL. Does physical activity prevent cognitive decline and dementia? A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. BMC public health. 2014 ;14(1):1-2.

- Firth J, Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, Schuch F, Lagopoulos J, Rosenbaum S, Ward PB. Effect of aerobic exercise on hippocampal volume in humans: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroimage. 2018;166:230-8.

- Chan D, Shafto M, Kievit R, Matthews F, Spink M, Valenzuela M, Henson RN. Lifestyle activities in mid-life contribute to cognitive reserve in late-life, independent of education, occupation, and late-life activities. Neurobiology of aging. 2018;70:180-3.

- Ngandu T, Lehtisalo J, Solomon A, Levälahti E, Ahtiluoto S, Antikainen R, Bäckman L, Hänninen T, Jula A, Laatikainen T, Lindström J. A 2-year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2015 6;385(9984):2255-63.