To mark European Public Health Week, Dr Jenny Mack, IPH Public Health Development Officer, explores the link between climate change and health in this blog about ‘Health, wealth and our planet’.

The modern world is incredibly convenient. At the click of a button, we can order practically anything for delivery to our door. The emphasis today is on speed and innovation, putting fast-food, fast-fashion, and smarter technology in our hands as quickly as possible. While this convenience is welcome given the everyday pressures of modern life, it is a double-edged sword.

Put plainly, consumerism and the rising demand for convenience has contributed to the destruction of natural resources, which in turn negatively impacts environmental and human health. Climate change and air pollution represent key symptoms of the natural world being stretched beyond its finite resources, and we are today witnessing a rise in deaths, diseases and injuries as heatwaves and floods take their toll.

There is an added layer of complexity given that the playing pitch is uneven. The social, economic, and environmental factors that influence how we live and our health – the social determinants of health – have contributed to a health gap between rich and poor. There is also the risk that this gap can be widened further by the activities of corporate actors for whom shareholder value, primarily profit, is the main priority. The manufacture, distribution, sale and marketing of unhealthy commodities heavily influence what we consume, and it is these influences that help determine the scale of health inequities[1].

But how do the commercial determinants of health impact the environment and climate change?

Let’s take the global food system as an example.

Since 1961, the supply of food calories per capita has increased by a third[2] and in recent decades we have also seen a dramatic increase in demand for calorie-dense, ultra-processed foods[3].

This has led to industrial food production on a massive scale, which has in turn led to substantial deforestation.

Today, the food industry, in particular meat and dairy production, contributes approximately 30% of global greenhouse gases[4].

Despite living in a world of plenty, 25-30% of food produced is lost or wasted[2] and world hunger remains, with an estimated 10% of the global population being undernourished in 2020[5].

At the same time, adult obesity has nearly tripled since 1975 and, alongside malnutrition, is a risk factor for non-communicable diseases, which account for 73.6% of global deaths each year[6].

These conditions also share several epidemiological similarities with climate change, which has led to the coining of these three threats as a ‘Global Syndemic’.[7]

Yet we see the continued proliferation and targeted marketing of foods that are high in fat, sugar and salt. There is also an irony in how positive initiatives, such as, city bike schemes, designed to encourage active travel, are frequently used as advertising vehicles for unhealthy products.

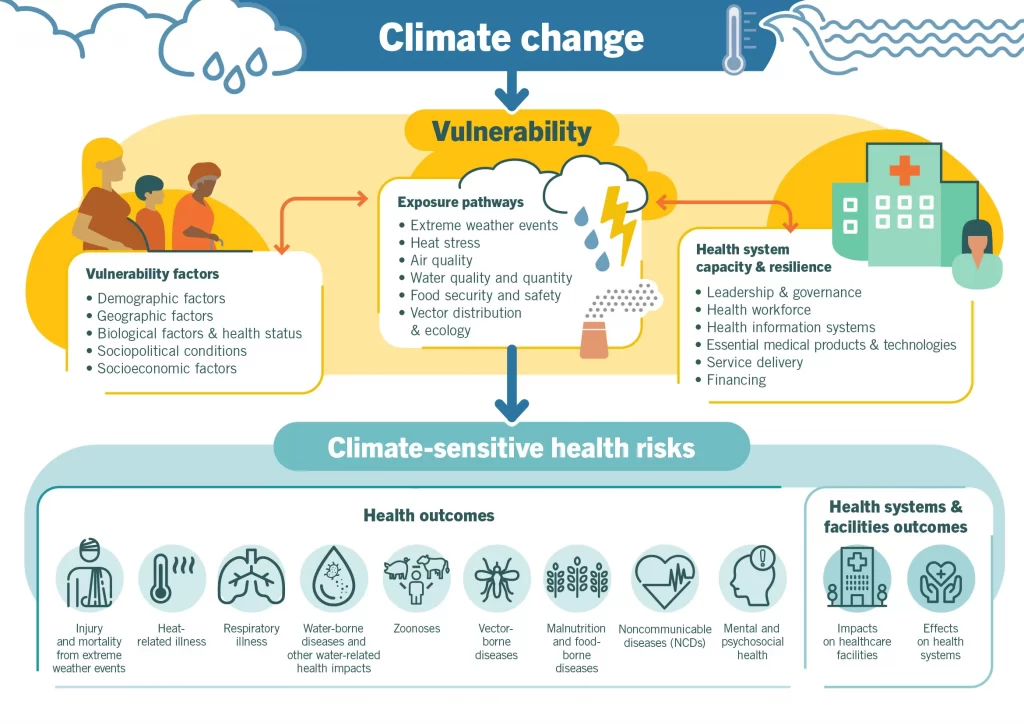

Figure: An overview of climate-sensitive health risks, their exposure pathways and vulnerability factors. Source: WHO

Figure: An overview of climate-sensitive health risks, their exposure pathways and vulnerability factors. Source: WHO

So how can you and I respond to the evolving challenges? Are there actions we can take, collectively or individually, to effect change and safeguard the environment and our health?

In short, the answer is yes. Given the degree to which the commercial determinants of health can shape our environment and our health, you could be forgiven for feeling powerless to make a difference. There is reason to be hopeful, however, as change is happening.

The World Health Organization is taking a leading role and has urged countries to set ambitious national climate commitments to sustain a healthy and green recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic[8]. At the global climate change summit, COP-26, last year over 50 countries committed to building climate-resilient and low carbon health systems[9].

As individuals, we also have the power to effect change and leverage the co-benefits of climate action.

To put it simply – actions that are good for the planet tend to also be good for our health and the health of future generations.

For example:

- Eat sustainably – Sustainable diets are associated with substantial co-benefits for the environment, but also for health. Processed meat and red meat are linked to increased risks of death from heart disease, diabetes, and other illnesses including cancer[10][11]. Reducing our meat consumption can reduce our risk of disease whilst also reducing the demand for livestock production.

- Breastfeeding – Evidence suggests that where possible breastfeeding is the best source of nourishment for infants and is a renewable natural resource[12]. Infant formula, however, has an environmental impact[12] and is heavily marketed to parents by a billion-dollar infant formula industry[13].

- Local produce – Buying local produce supports the local economy while reducing the need to import foods and the high carbon footprint associated with some produce.

- Active travel – By opting for active travel options where we can, such as walking or cycling, there is a personal physical activity dividend to be gained which can help to reduce the risk of major non-communicable diseases, including mental illness and stress[14][15], whilst also limiting air pollution.

In summary, we cannot afford to disregard the power we hold as consumers to change the status quo in favour of the environment and our health. We must recognise and promote the co-benefits that can be harnessed from actively responding to the climate crisis, while also reducing the impact of unhealthy commodity industries and unsustainable consumption.

Given the scale of the challenge, co-operation and partnership working is essential. To that end, the Institute of Public Health is delighted to announce plans for an all-island conference on climate change and public health in November 2022. The North-South conference, hosted in collaboration with local health partners, aims to raise the profile of public health research, interventions, and innovation relevant to climate change and health and further details will be announced in the coming months.

If you would like to keep up to date with plans for this conference or other IPH activities you can subscribe for our regular updates and newsletters here.

References

[1] World Health Organization (2021). Commercial determinants of health. Geneva, World Health Organization.

[2] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2019). Climate Change and Land. An IPCC Special Report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems. Summary for Policymakers. Geneva, IPCC.

[3] Branca, F., Lartey, A., Oenema, S., Aguayo, V., Stordalen, G. A., Richardson, R., Arvelo, M., & Afshin, A. (2019). Transforming the food system to fight non-communicable diseases. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 364, l296.

[4] United Nations (UN) (2021). “Food systems account for over one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions.” from https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/03/1086822.

[5] World Health Organization (2021). “UN report: Pandemic year marked by spike in world hunger.” from https://www.who.int/news/item/12-07-2021-un-report-pandemic-year-marked-by-spike-in-world-hunger.

[6] World Health Organization (2020). WHO methods and data sources for country-level causes of death 2000-2019. Geneva.

[7] Swinburn, B. A., et al. (2019). “The Global Syndemic of Obesity, Undernutrition, and Climate Change: The Lancet Commission report.” Lancet 393(10173): 791-846.

[8] World Health Organization (2021). “WHO’s 10 calls for climate action to assure sustained recovery from COVID-19.” from https://www.who.int/news/item/11-10-2021-who-s-10-calls-for-climate-action-to-assure-sustained-recovery-from-covid-19.

[9] World Health Organization (2021). “What has COP26 achieved for health?”. from https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/what-has-cop26-achieved-for-health.

[10] NHS (2021). “Meat in your diet.” from https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/eat-well/food-types/meat-nutrition/.

[11] World Health Organization: International Agency for Research on Cancer (2015). IARC Monographs evaluate consumption of red meat and processed meat. Lyon.

[12] Joffe, N., et al. (2019). “Support for breastfeeding is an environmental imperative.” BMJ 367: l5646.

[13] UNICEF United Kingdom (2022). “How Marketing of Formula Milk Influences our Decisions on Infant Feeding: A Report by The WHO And UNICEF.” London.

[14] Public Health England. Working Together to Promote Active Travel: A briefing for local authorities. London; 2016.

[15] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Physical activity: walking and cycling: NICE; 2021 [Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph41/chapter/1-Recommendations.